Deep in the forest, beneath our feet and hidden from human eyes, an incredible conversation is taking place. Trees, those silent giants we pass by every day, are actually chatting away with their neighbors, sharing resources, and even caring for their young. It’s a fascinating story that will forever change how you look at your backyard maple or the forest down the street.

A mother tree, tall and mighty, stands in the heart of the forest. Her branches stretch toward the sky, but it’s what’s happening underground that will blow your mind. Through a web of tiny fungal threads thinner than a strand of hair, she’s sending sugar, water, and a whole bunch of nutrients to her saplings – her tree babies – growing in the shade nearby.

But here’s where it gets even cooler. These trees aren’t just helping their own kids. They’re part of what scientists now call the “Wood Wide Web,” an underground network that connects hundreds of trees in the forest. Just like we use the internet to share messages and help each other out, trees use this fungal network to support their entire forest community.

Take what happened in a forest in British Columbia, Canada. Scientists discovered that when paper birch trees had plenty of sugar (which they make through photosynthesis during summer), they shipped the extra food to nearby Douglas fir trees that were struggling in the shade. Then, when autumn came and the birch trees lost their leaves, the Douglas firs returned the favour by sharing their resources. Talk about being a good neighbour!

But trees don’t just share food. They’re also the forest’s warning system. When a tree gets attacked by insects, it sends out chemical signals through the air and underground network to warn its neighbours. The other trees pick up these stress signals and start beefing up their defences by making their leaves less tasty to insects. It’s like they’re sending text messages saying, “Watch out! Bugs are coming!”

The most mind-blowing part? Old, large trees (forest scientists call them “hub trees” or “mother trees”) can be connected to hundreds of other trees. These wise old giants act like the forest’s social media influencers, sharing resources and information with younger trees. When these mother trees sense they’re dying, they even send their remaining resources to their neighbours, like a final gift to the community.

Dr. Suzanne Simard, the forest scientist who discovered much of this tree communication, found that a single mother tree can be connected to hundreds of other trees. In one patch of forest the size of a football field, all the trees might be linked in one huge social network. It’s like Facebook for forests!

But this isn’t just a cool science fact – it’s changing how we think about forests. For years, we thought trees were just standalone plants competing for sunlight and water. Now we know they’re part of a caring, sharing community that looks after its members. They’re more like a close-knit family than a bunch of strangers fighting for resources.

Here’s something that might surprise you: Trees even seem to recognize their relatives. Research shows that trees reduce competition with their siblings by growing their roots in a way that gives their family members more space and resources. It’s as if they’re saying, “Hey, that’s my sister over there – let’s make sure she has enough room to grow!”

This discovery has huge implications for how we manage our forests. Clear-cutting (removing all trees from an area) doesn’t just take away trees – it destroys these amazing underground networks that have taken decades or even centuries to develop. It’s like ripping out the forest’s social security system.

The good news is that more forest managers are now working to protect these networks. They’re leaving mother trees standing when they harvest timber and making sure underground connections stay intact. Some are even mapping these tree networks to identify and protect the most connected hub trees.

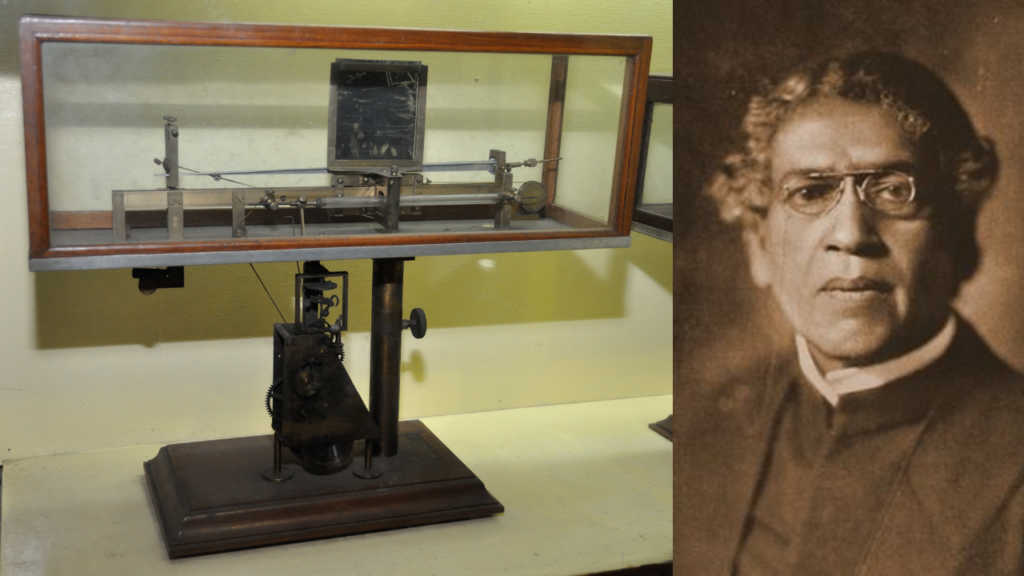

While these discoveries seem revolutionary today, a very famous Indian scientist named Dr. Jagadish Chandra Bose was actually the first to scientifically prove that plants have life and feelings, way back in the early 1900s. At a time when most scientists dismissed the idea of plant consciousness, Dr. Bose invented incredibly sensitive instruments that could detect minute tremors and responses in plants. His groundbreaking “crescograph” could magnify a plant’s movement by ten million times, showing how plants responded to stimuli, felt pain, and understood affection. Despite facing scepticism from the Western scientific community, Dr. Bose persisted, demonstrating that plants have a nervous system and can “feel” their surroundings. He showed that plants grew more quickly when exposed to pleasant music and could wither when exposed to negative thoughts or harsh treatment. His revolutionary work laid the foundation for our modern understanding of plant communication and behaviour, proving over a century ago what scientists are still discovering today – that plants are far more aware and alive than we ever imagined.

Next time you walk through a forest or past a group of trees, remember: you’re not just looking at a bunch of individual plants. You’re witnessing a living, breathing community where members look out for each other. Those trees might look like they’re just standing there, but underground they’re busy sharing resources, sending warnings, and caring for their young.

In a world where we often feel disconnected from nature and each other, these discoveries remind us that cooperation and caring for others isn’t just a human trait – it’s woven into the very fabric of life on Earth. The trees have known this all along. Maybe it’s time we started listening to what they’ve been trying to tell us.